SENSORY LABOR

What does it mean to have good taste in a society where the 'natural' experiences of tasting are deeply designed and shaped by technological innovation, market pressures, and regulatory structures? What forms--and methods--of sensory labor are welcomed into systems and structures of policy making, and what forms of sensory labor are excluded?

The sensory labor(atory) project--which spans across my research and teaching--is grounded in disrupting everyday sensory labor. Disruption draws attention to the daily work done by mouths, noses, hands, ears, and eyes, while also highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of historically grounded expert modes of sensing.

The sensory labor(atory) project--which spans across my research and teaching--is grounded in disrupting everyday sensory labor. Disruption draws attention to the daily work done by mouths, noses, hands, ears, and eyes, while also highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of historically grounded expert modes of sensing.

DISRUPTIONS

Disruptions build not only on comparative historical approaches, and ethnographic fieldwork, they also draw on performance art as well as critical and speculative design practices to breach or upend familiar everyday experiences. Through low-resolution prototyping, as well as the use of found objects, I--and my students--raise awareness of the assumptions built into twentieth-century sensory labor practices, while highlighting the politics built into how one senses.

Currently, I am working on a series of disruptions centered on taste and smell in conjunction with (and generously funded by) the Hixon-Riggs Program for Responsive Science and Engineering (housed at Harvey Mudd College) and the Rick and Susan Sontag Center for Collaborative Creativity.

Currently, I am working on a series of disruptions centered on taste and smell in conjunction with (and generously funded by) the Hixon-Riggs Program for Responsive Science and Engineering (housed at Harvey Mudd College) and the Rick and Susan Sontag Center for Collaborative Creativity.

|

|

Tasting & Talking Technology

co-organized with Stephanie LaFace, Griffin Paisley, and Tiffany Sun

4.6.16

co-organized with Stephanie LaFace, Griffin Paisley, and Tiffany Sun

4.6.16

Ingesting the Informational Imaginary

co-organized with Rebecca Uchill; including Krithika Ramchander [MIT], spurse collective, and Elizabeth Hoover [Brown]

9.3.17

This 60-minute lunchtime workshop brought together a small group of interdisciplinary practitioners: STS scholars, artists, and scientists to offer ingestible “disruptions” as a means of sharing information and research. These sensorial offerings (tastings, sounds, images) made sense-able the conditions, infrastructures, and forms that define the quotidian; they asked participants' bodies to question how they “know” what they ingest, to use their senses to bring the techno-scientific infrastructures—such as engineering, data management, regulation—into focus. With mushrooms, pears, and carbon dioxide, participants “imagined” the information typically kept beyond the human sensorial grasp. Neither entirely a meal, nor entirely a demo, this workshop integrated the methods of science/art studies to offer a range of access points to knowing the information offered, and hidden, by sensing.

co-organized with Rebecca Uchill; including Krithika Ramchander [MIT], spurse collective, and Elizabeth Hoover [Brown]

9.3.17

This 60-minute lunchtime workshop brought together a small group of interdisciplinary practitioners: STS scholars, artists, and scientists to offer ingestible “disruptions” as a means of sharing information and research. These sensorial offerings (tastings, sounds, images) made sense-able the conditions, infrastructures, and forms that define the quotidian; they asked participants' bodies to question how they “know” what they ingest, to use their senses to bring the techno-scientific infrastructures—such as engineering, data management, regulation—into focus. With mushrooms, pears, and carbon dioxide, participants “imagined” the information typically kept beyond the human sensorial grasp. Neither entirely a meal, nor entirely a demo, this workshop integrated the methods of science/art studies to offer a range of access points to knowing the information offered, and hidden, by sensing.

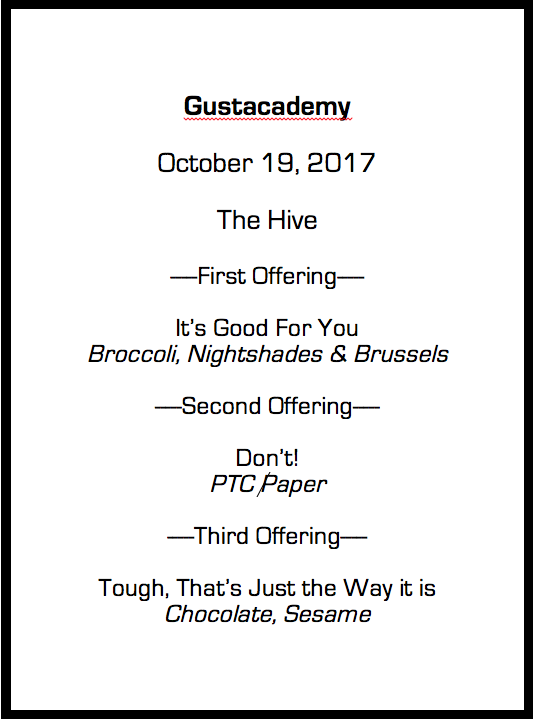

Gustacademy

Co-organized with the students of STS179D: Technologies of Taste

10.19.17

Childhood. A time of learning and experimentation, of using whatever utensils one wishes—hands, mouths, forks, sticks—childhood is the point where we came to know and articulate within the realms and norms of society, where we were trained, socialized, and required to eat in just that way (Mann and others, 2011). One learns to taste and eat as a child, to articulate likes and dislikes. At times those likes and dislikes were sovereign, after all, consider the resistance found in a toddler refusing to eat. At times those likes and dislikes were ignored, rendered powerless against the structures around them. Our opinions, as children, were both allowed and circumscribed.

As adults, we too find our opinions allowed and circumscribed. What happens when one plays around with the sensory science practice of sifting and sorting people based on their “ability” to sense? When one takes adults and places them again as children until a test, rooted in genetics, sorts them into super-tasters and non-tasters, and in the process creates new power structures where some information is taste-able, and other disappeared?

Co-organized with the students of STS179D: Technologies of Taste

10.19.17

Childhood. A time of learning and experimentation, of using whatever utensils one wishes—hands, mouths, forks, sticks—childhood is the point where we came to know and articulate within the realms and norms of society, where we were trained, socialized, and required to eat in just that way (Mann and others, 2011). One learns to taste and eat as a child, to articulate likes and dislikes. At times those likes and dislikes were sovereign, after all, consider the resistance found in a toddler refusing to eat. At times those likes and dislikes were ignored, rendered powerless against the structures around them. Our opinions, as children, were both allowed and circumscribed.

As adults, we too find our opinions allowed and circumscribed. What happens when one plays around with the sensory science practice of sifting and sorting people based on their “ability” to sense? When one takes adults and places them again as children until a test, rooted in genetics, sorts them into super-tasters and non-tasters, and in the process creates new power structures where some information is taste-able, and other disappeared?

Proudly powered by Weebly